Paediatric Research: The Plotkin Institute (ULB) and HUDERF at the forefront of the global fight against Group A Streptococcus

No safe and effective vaccine has yet been developed, but since 2018 the WHO has made vaccine research against Group A Streptococcus a global priority.

The European Plotkin Institute of Vaccinology (epiv.eu) brings together research teams in immunology and microbiology to address infectious diseases in Belgium and worldwide. Within this framework, Dr Gabrielle de Crombrugghe, paediatrician at the Queen Fabiola Children’s University Hospital (HUDERF) and FNRS Fellow, conducts major scientific research on Group A Streptococcus, a bacterium responsible for more than half a million deaths every year.

Her project is based on an integrated approach:

• one year of clinical research in Gambia, at the Medical Research Council, to study transmission patterns, strain diversity and immune responses;

• the analysis of samples at the Plotkin Institute, where she explores the microbiological and immunological aspects of infection, drawing on the expertise of the teams led by Professors Anne Botteaux, Pierre Smeesters and Arnaud Marchant.

International recognition

In 2024–2025, Dr Gabrielle de Crombrugghe’s work resulted in several publications in leading scientific journals:

The Lancet Microbe The Lancet Microbe 2 The Lancet Microbe 3 Nature Medicine Journal of Infectious Diseases Clinical Microbiology and Infection

These studies provide crucial data to guide the development of a global vaccine against Group A Streptococcus, which is now considered a priority by the World Health Organization.

Interview – Dr Gabrielle de Crombrugghe, paediatrician and researcher at the Plotkin Institute

Group A Streptococcus remains a major cause of severe infections worldwide. What makes this bacterium so dangerous, particularly for children?

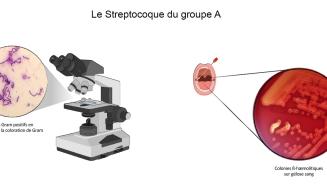

Group A Streptococcus (or Strep A) kills half a million people worldwide every year, mainly in low- and middle-income countries, with the highest mortality observed in sub-Saharan Africa. This bacterium causes a wide range of illnesses, from superficial infections such as throat infections and impetigo, to invasive diseases including meningitis, pneumonia and bloodstream infections.

The main cause of mortality, however, is due to autoimmune complications, particularly in younger patients, in which the immune system turns against the host and damages the heart valves, leading to heart failure. This autoimmune disease is the leading cause of acquired heart disease in children and adolescents worldwide. It has almost disappeared in high-income countries but remains a major cause of mortality in low- and middle-income regions.

As a paediatrician and a mother, I have been interested in this bacterium for several years, as it primarily affects children and adolescents. Strep A is a complex pathogen that manages to evade the immune system, is sometimes difficult to treat effectively and, importantly, still has no available vaccine.

You divide your time between Gambia and the Plotkin Institute of Vaccinology in Anderlecht. How do you combine fieldwork with laboratory research in your daily routine?

Sub-Saharan Africa records the highest mortality linked to Strep A, yet there is very limited information on how the bacterium circulates in this region. To develop an effective vaccine for these settings, it is essential to understand the diversity of serotypes circulating locally.

As part of my PhD, I took part in the SpyCATS study (Streptococcus Pyogenes Carriage Acquisition and Transmission Study), which followed the diversity of circulating strains for 12 months in a community of 400 people in Sukuta, Gambia. The study analysed transmission mechanisms and the way the immune system responds to infections.

I spent 12 months in Gambia coordinating fieldwork, medical assessments and sample collection. At the end of the study, I returned to the molecular bacteriology laboratory at the Plotkin Institute. Most samples were analysed locally at the Medical Research Council Gambia (MRCG), while part of the collection was transferred to Brussels for specific analyses under the supervision of Professors Anne Botteaux, Pierre Smeesters and Arnaud Marchant.

Despite my return to Brussels, collaboration between our laboratory and the MRCG remains very active. I travelled back to Gambia last month as part of this partnership — and took the opportunity to introduce my son, born at the end of the study, to my Gambian colleagues and the participating families.

The MRCG is a leading research centre in West Africa and has collaborated with the Plotkin Institute teams for many years. After my PhD, I will return to the Queen Fabiola Children’s University Hospital (HUDERF) as a paediatrician, and I hope to continue working with the MRCG on the scientific front.

Your work has been published in The Lancet Microbe, Nature Medicine and the Journal of Infectious Diseases. What are the most significant findings to emerge from this research?

Our work has highlighted the lack of epidemiological data from low- and middle-income countries, particularly from sub-Saharan Africa, where mortality linked to Strep A is highest. Robust observational studies are therefore essential to better understand how this pathogen behaves in these regions and to ensure that a future vaccine will be effective.

The SpyCATS study enabled us to analyse the diversity of circulating serotypes, showing that it is considerably higher than what is observed in high-income countries. We also revealed the major role of skin infections, which are predominant in Gambia — a very different situation from our context, where throat infections are most common. Transmission mechanisms therefore seem to vary across populations and must be taken into account in vaccine development.

We also underscored the importance of asymptomatic carriage in the throat or on the skin — which causes no symptoms for the carrier, but can lead to infection if transmitted to someone else. Our study, which uniquely included a wide age range from newborns to grandparents, also revealed crucial differences between children, who are far more susceptible to infection, and adults. Analysing natural immune responses at different ages is particularly promising for some of the vaccine candidates currently under investigation.

You are working towards the development of a vaccine against Group A Streptococcus. What are the main avenues or hopes in this field today?

Despite a century of research, no safe and effective vaccine has yet been developed. The major challenge lies in the extensive diversity of strains — with more than 200 circulating serotypes. However, since 2018 the WHO has made Strep A vaccine research a global priority and hopes to achieve a viable vaccine by 2035.

International teams are collaborating on the development of vaccine candidates, exploring different proteins as potential targets and seeking to better understand the immune mechanisms that provide protection. An Australian human challenge study, in which healthy volunteers were deliberately inoculated with Strep A to study their immune responses, together with observational studies such as SpyCATS, helps shed light on the immune mechanisms that protect against infection.

These data are essential to guide vaccine development and accelerate progress towards a safe and effective vaccine.